SPECIAL REPORT: Data Tariffs

A Brief for Clients and Stakeholders

Executive Summary

· The United States (US)-based tech conglomerates (an industry sector colloquially referred to as “Silicon Valley”), not the primary players in the United States (US) federal government, are the determiners of tariff policy as it relates to data flows. The behavior of the firms and the industry as a whole thus influences the types of data-based trade that appear to be in the interests of the US and Washington.

· Silicon Valley promotes greater barriers to data-based trade through its retaliatory stance towards other developed markets, particularly Europe following the implementation of the European Union’s (EU) General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

· The global economy has and will continue to suffer under the currently understood parameters of US-implemented data tariffs, namely in the heightened storage costs for data in the US and the cost of limiting activities in the world’s largest market that may result.

· Uncertainty and increased costs associated with US tariffs and related trade barriers on data represent an opportunity for China to gain a foothold in many global markets and become a more sizable presence in the data-based tech industries.

Introduction

The end of the laissez-faire trade policy regime in the global and transatlantic relationships is the seminal trend of contemporary international business. This is best seen in the strident, increasing, and often unpredictable threats of substantial tariffs levied by the US government, particularly under the two Trump administrations.[1] Given that this situation has a yet to be determined end – or a more stably established new trade policy regime as a result[2] – the issue of tariffs is naturally closely watched by many business observers, particularly in critical developed markets in Europe and Asia.[3]

This brief will focus on what is perhaps the most difficult to understand yet essential pillar of global trade flows: the transfer and use of data and data-powered digital technologies across borders. Here, it is clear that the influence of Silicon Valley is at a high point, as described by the previous Biden administration as a “tech-industrial complex” that has come to dominate economies both domestic and international.[4] This makes the use of tariffs a “powerful bargaining chip”[5] in determining global tech and trade policy, as well as an expression of grievance and animosity towards prevailing international trade regimes (especially in Europe). In this way, we see the American position on protectionism as a response to Republican perceptions of “extortion” and “censorship” that take undue advantage of prior openness in relations with allied nations such as those benefitting from US investment in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).[6]

Barriers to Trade

Based on the above background, markets operate in an environment less conducive to trade and shared economic activity across borders. Traditionally, this has been most encapsulated through tariffs, a policy direction that importantly constitutes much of the early sources of government revenue for the US as it developed into a world power in the nineteenth century.[7] In the case of taxing data, however, there are multiple areas where tariffs may be placed, though two areas are the most straightforward and impactful to the global marketplace:

1. Taxes may be levied on quantities of data that are directly entering the country, and such levies often prove quite substantial given the ever growing value of data in the highly networked commercial economic environment of the twenty-first century.

2. Data tracked on networks requires physical infrastructure for storage, processing, and transfer,[8] and these products may be similarly taxed, particularly when packaged in the rhetorical context of protecting American domestic sourcing and manufacturing.[9]

In an effort to blunt the perceived effect of trade barriers on publics who might otherwise have a historical inclination towards a neoliberal free trade approach,[10] the tech and trade policy communities are actively pursuing limiting international trade in ways accomplished beyond the reach of tariffs. This is not only attractive as a means of lowering taxation – a generally popular policy stance[11] – but also appeals to traditional American values of “freedom of speech”[12] by allowing “American” data to fully spread itself with less competition in the marketplace. There is additionally the benefit of propping up domestic digital infrastructure industries that put these policies into practice.

Therefore, “non-tariff barriers” in this area include some of the following:[13]

· Restricting data flows across borders;

· Imposing requirements to localize data infrastructure;

· Taxing digitally-created goods/services that exist in American networks;

· Regulating innovation to ensure maximum access and opportunity for American entities;

· Limiting the use of certain cloud service providers whose business creates an undue challenge to the profitability of US firms and their products.

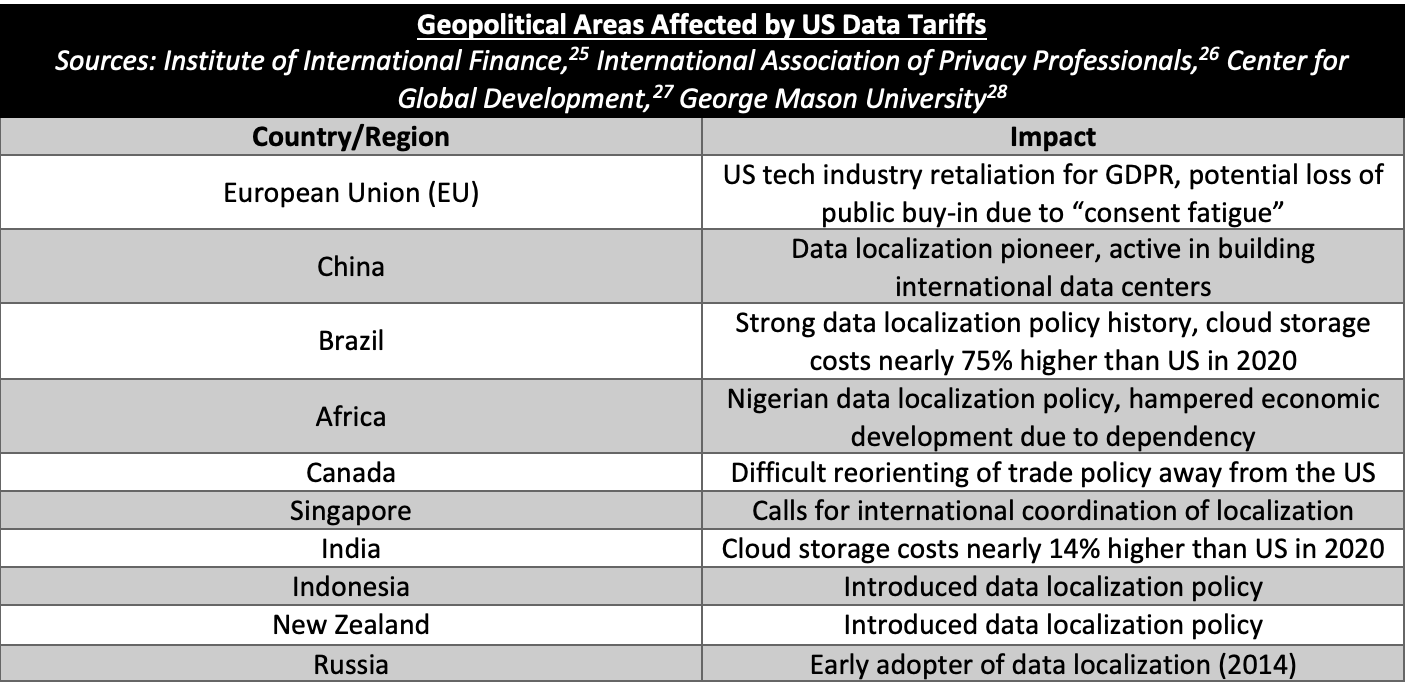

It is clear that restricting data flows is an attractive option for the protectionist US tech industry. The policy preference for those with such interests is data localization, or the requirement to physically store data within the recognized boundaries of a home market (in this case, the US).[14] Such policies are popular throughout the world and have been most fully implemented in China[15] (see table below) but it remains to be seen whether such a direction will have similar “benefits” in more open, less isolated markets like the US. The policy and business reasoning for such data localization centers on the following desired effects:[16]

1. The prevention of valuable data from leaving country or its domestic market or its access by firms based in the domestic market;

2. The guarantee of appropriate access to relevant data by domestic law enforcement, who can more actively pursue cases of fraud and cybersecurity breeches;

3. The growth of national tech talent technology through the imposition of demand by a “data center economy;”

4. The protection of citizen data privacy.

Data localization policies and their effects incorporate several unique features that alter the political economy landscape of international trade. It is important to note that some globalized industries use more data and are thus more susceptible to tariff and non-tariff barriers to data flows. These industries include:[17]

· Financial services;

· Manufacturing;

· Healthcare;

· E-commerce

· Cloud computing components, infrastructure, and platforms that make data-driven businesses possible.

Taken together, these industries take up an outsized portion of the world economy, with an output on par with some of the most developed (G7 nations) economies on earth. Adding to the cost is the fact that storing data without using it involves using finite energy resources to construct advanced infrastructure with a limited profit stream supporting such an enterprise.[18] This profit stream is especially limited as data localization makes it difficult to transfer important personal information (like credit histories) across borders.[19] As such, a common data localization requirement for foreign firms is the requirement to keep a copy of a firm’s proprietary data on a domestic server.[20],[21]

This highlights how the use of data localization policy, while enriching individual businesses (especially in the US), executives, and related interests, holds many drawbacks for the global tech industry and the economy as a whole. Chief among these concerns is the dramatic increase in cost for hosting and sending data that such regulations impart on data providers and data infrastructure companies, as evidenced in the de facto duplication of data required for firms to meet data localization standards. At the same time, these organizations lose significant access to meaningful profit motive as data flows slow down and access to new customers, advanced technologies (namely algorithms), and systems development becomes more stalled.[22] From a security perspective, this is most concerning as fragmented data systems without coordinated communication constitute a recipe for cyber threats – particularly as dictated by geopolitical considerations – to thrive.[23]

Importantly, data localization standards do not have to be codified into specific law for these effects to take place. This is due to complex arrangements enforced by political power or cartel-like industry agreements and their consequent alignment of special interests, which can overwhelm efforts from smaller firms to continue to engage in free-flowing data practices This is especially true if such efforts require the utilization of tech resources controlled by the largest tech firms. Such a plutocratic and de facto authoritarian stance erodes trust in the data-sharing system over time, thus undermining a fundamental building block of the big data economy. That said, there is some hope that digital identity and data tracing may represent a compromise solution to more effectively engage the special interests in question and better utilize human talent in information technology in the US and globally.[24]

Markets Affected

The table above clearly shows how the trend of data protectionism is truly global in scope and appears to be a popular topic for national governments to consider as they look to leverage data ownership into nationally valuable assets. Among the various countries where data localization – and a turn towards data tariffs and non-tariff data trade barriers - has taken hold, four regions stand out:

1. In Europe, the GDPR has made an outsized impact on the perception of data and tech industries on conducting their respective businesses with greater costs of maintenance and entry. This is due to the preponderance of “digital sovereignty” priorities throughout the continent, and especially in the states that are part of the EU.[29] Thus the “EU views personal data as a critical commodity in the digital age.”[30] Notably, the two largest EU powers of France and Germany are firmly aligned in this policy area, driving its development, maturation, and implementation. This extends to the use of “European” data for social and economic profit purposes, particularly when it comes to artificial intelligence (AI). From this point of view, “European” AI products and systems should be trained on “European” data that employs “European” cloud computing capabilities such as the Gaia-X system that could displace the use of foreign firms’ data storage products from profitably operating in the EU.[31] In this way, many stakeholders – specifically the large tech powers in places such as Silicon Valley – naturally view GDPR as “bad for competition and consumer choice” because it “erects an international barrier to trade” and thus “serves as a kind of tariff” on data-driven products and services. Part of this opposition comes from concerns that users may have “consent fatigue” and that there are associated costs to keep users engaged when they have to constantly approve legal terms of service, and another part of this concern is that GDPR is seen as too vague to consistently define and enforce “compliance.”[32]

2. In China, there is a model taking shape that represents a direct challenge to the business of Western tech firms and the data-driven economies of the Western countries they occupy. This risk is centered around the fact that dependence on China is easy for many countries today given the structure of global trade flows.[33] Here, there is a cost for a country or foreign firm to leave the reach of the Chinese market, namely in sourcing and building the infrastructure to store data and use if in domestic (or non-Chinese) contexts.[34] This reality is not new given China’s pioneering approach to data localization policy over many years,[35] representing an example for other jurisdictions to follow as the impact of Chinese-developed data policies become multiplied in an age of growing global protectionism. This effect is also seen as China increases its international influence and penetration in new international markets, especially those in the developing world.[36] As such, “there is some concern that China will be willing to subsidize installation of data centers in various countries as required by data localization laws. Even if not strictly economically justified, it could give China a means to access such data for intelligence purposes.”[37] All of this may also be done in tandem with effective Chinese efforts to box out competition from non-Chinese entities both in China and abroad.[38]

3. In Canada, the socioeconomic environment is often dependent on the policy and economic trajectories of its huge southern neighbor, the US. In this way, trade agreements with the US have a significant influence over upcoming trends in the Canadian economy. Outsize recent controversies regarding a rehashing of Reagan-era anti-tariff policies,[39] a most recent renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) addresses the data-driven economy directly by establishing a “continental digital services market.”[40] That said, tariff policies from Washington – largely employed in an unpredictable fashion – provide some upheaval for this market, prompting Canadians to take more drastic actions it its trade policy. This importantly includes pivoting data trade and regulation with interactions with Europe and Asia as AI and associated privacy standards concerns emerge as growing priorities for society.[41]

4. In Africa, countries remain vulnerable to the unpredictability and lack of control over the actions of policymakers and tech companies outside the continent. This is particularly evident in the activities of China in multiple African countries that have received Chinese aid for national-level surveillance and censorship initiatives that leverage advanced technologies and big data to promote security and economic growth.[42],[43] However, following the Chinese model of data localization has very negative effects for African countries because many are less developed and less connected to the global tech economy. This creates a greater burden to overcome when it comes to international aid and development strategies to keep these countries afloat, a burden that continues apace as these smaller markets are forced to accept the data policy rule of order established from larger tech policy interests and powers.[44]

Conclusion

The imposition of trade barriers in data-driven industries is clearly part of a broader wave of protectionism facing the world economy. It is also the product of special interests driving policy in the US, where the reach of Silicon Valley towers above international business dealings. It is equally important to acknowledge that China is a major influencing power and a model for data localization policies that have become more widespread globally, even in the traditionally free trade culture of the US.

Clients and stakeholders associated with large and valuable data holdings should be mindful of how China and Silicon Valley (via the Trump administration) look to shape the nature and possibilities for curtailing international data flows.

· In the Chinese case, there is a likelihood that advanced data storage and processing infrastructure could be dominated by Chinese firms with an imprint in markets around the world, providing meaningful competition driving customers away from Silicon Valley products and solutions. At the same time, the perceived effectiveness of Chinese data localization policy (as a potential conduit for China’s meteoric rise as a tech and economic power)[45] presents a viable threat to put the world under crippling data tariffs and non-tariff barriers as a result of reciprocal policy practices.

· When examining the risks coming from US firms, it is clear that clients and stakeholders must equally balance whether to accept trade barriers on their data as a consequence of maintaining reliance on the world’s largest market. This has potentially uncertain and damaging implications as the Trump administration continues its whipsaw international trade policy directions.

Yet it remains evident that Silicon Valley holds the greatest interest and potential to influence in setting data-related tariffs and associated protectionism in the US market. It also appears that Silicon Valley is in a retaliatory mood towards states whose data policies do not align with its business directions. With this in mind, clients and stakeholders in Europe, Asia, and beyond are thus correct to engage in serious conversations about the positions they wish to take as data localization and similar tariff/tariff-esque policies become more entrenched in the central, world-setting economy of the US. These conversations should employ a calculus that is more global in scope with an understanding that non-state institutions (like the businesses that make up the Silicon Valley tech sector) have the power to set policy based on well-communicated and consistent interests and preferences. As such, uncertainty in the regulation of data across borders, may decrease among business and political leaders internationally, a result that can stabilize markets in a complex economic age.

[1] “A Timeline of Trump’s Tariff Actions so Far.” PBS News, 3 Apr. 2025, www.pbs.org/newshour/economy/a-timeline-of-trumps-tariff-actions-so-far.

[2] West, Rachel, and Laura Valle Gutierrez. “Trump’s Tariffs and Economy of Uncertainty Are Already Causing Pain.” The Century Foundation, 5 Aug. 2025, tcf.org/content/commentary/trumps-tariffs-and-economy-of-uncertainty-are-already-causing-pain.

[3] Suthenthiran, Anusha. “US Tariffs and the Uneven Impact Across Cities in Europe and Asia.” Oxford Economics, 12 Aug. 2025, www.oxfordeconomics.com/resource/us-tariffs-and-the-uneven-impact-across-cities-in-europe-and-asia/#:~:text=Uncertainty%20remains%20high%20for%20the,tariffs%20across%20regions%20and%20industries.

[4] Bomont, Clotilde. “Trump takes aim at ‘overseas extortion’ of American tech companies: the EU-US rift deepens.” European Union Institute for Security Studies, 27 February 2025. https://www.iss.europa.eu/publications/commentary/trump-takes-aim-overseas-extortion-american-tech-companies-eu-us-rift

[5] Kilic, Burcu. “Between Tariffs and Tech: What Will Europe Choose?” Bot Populi, 27 June 2025. https://botpopuli.net/between-tariffs-and-tech-what-will-europe-choose/

[6] Bomont

[7] “History of Tariffs .” American Historical Association, www.historians.org/resource/history-of-tariffs/#:~:text=At%20any%20point%20in%20time,trade%20agreements%20with%20other%20countrie

[8] Phillips, Stephen, Ramesh Razdan, and Matthew Leybold. “Tariffs are Reshaping Tech Functions as Deglobalization Accelerates.” Bain and Company. https://www.bain.com/insights/tariffs-are-reshaping-tech-functions-as-deglobalization-accelerates/

[9] “History of Tariffs”

[10] “Fact-checking Claims That a Canadian Ad Was Misleading About Reagan’s Tariff Warning.” PBS News, 26 Oct. 2025, www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/fact-checking-claims-that-a-canadian-ad-was-misleading-about-reagans-tariff-warning.

[11] Newport, Frank. “Where Americans Stand on Taxes.” Gallup.com, 16 Oct. 2024, news.gallup.com/opinion/polling-matters/652151/americans-stand-taxes.aspx#:~:text=Americans’%20views%20on%20whether%20their,4.

[12] Kilic

[13] Ibid

[14] French, Conan, Brad Carr and Clay Lowery. “Data Localization: Costs, Tradeoffs, and Impacts Across the Economy.” Institute of International Finance, December 2020. https://www.iif.com/portals/0/Files/content/Innovation/12_22_2020_data_localization.pdf

[15] Vogt, William J. Foundations of the Chinese Internet: Calculations, Concepts, Culture. Kendall Hunt, 2023.

[16] French

[17] Ibid

[18] Ibid

[19] Medine, David. “Data Localization: A “Tax” on the Poor.” Center for Global Development, January 2024. https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/data-localization-tax-poor.pdf

[20] Ibid

[21] Phillips

[22] French

[23] Phillips

[24] French

[25] French

[26] Karbaliotis, Constantine. “Notes from the IAPP Canada: Tariff threats raise US-Canada data flow concerns.” International Association of Privacy Professionals, 24 January 2025. https://iapp.org/news/a/notes-from-the-iapp-canada-tariff-threats-raise-us-canada-data-flow-concerns

[27] Medine

[28] De Rugy, Veronique and Andrea O’Sullivan. “The Tariff No One Is Talking About.” Mercatus Center (George Mason University), 17 July 2018. https://www.mercatus.org/economic-insights/expert-commentary/tariff-no-one-talking-about

[29] French

[30] De Rugy

[31] French

[32] De Rugy

[33] “The Strategic Challenges of Decoupling.” Harvard Business Review, 1 May 2021, hbr.org/2021/05/the-strategic-challenges-of-decoupling.

[34] Phillips

[35] Vogt

[36] Vogt, William J., Guilan Massoud-Moghaddam, and Robert Chong. “Sino-Lusophone Relations in the Information Age: A Key Diplomatic Case Study.” Observa China, 2025. https://www.observachina.org/en/articles/relacoes-sino-lusofonas-na-era-da-informacao

[37] Medine

[38] Ibid

[39] “Fact-checking”

[40] Karbaliotis

[41] Ibid

[42] Phillips

[43] Medine

[44] Ibid

[45] Vogt (2023)